“We were inundated by instruments that almost always measured impairments. We eschewed the ‘soft’ behavioral measures that reflected disabilities in favor of the seemingly more scientific measurements of impairments. We forgot to balance the elements to find the middle ground.” Jules Rothstein, APTA Journal Editor, 1994

There always seems to be those persons and organizations that want to thrive on picking the low hanging fruit instead of doing the heavy lifting and climbing associated with “true” cost containment and clinical outcomes advancement. This “principle of least effort” is not restricted to describing teenagers and their messy rooms, household chores and homework. The principle of least effort has been associated with nomadic tribes who after exhausting local resources, packed up and moved on to the next environment where the cycle repeated itself. These early ancestors did not engage in agrarian culture because clearing land, tilling soil, planting and harvesting crops is hard work. That is why farmers work from sunrise to sunset.

Despite the overwhelming complexity of medical systems for some unknown reason[s]; this sector seems to invite “quick fixes”, “one-size-fits all” strategies and searches for the next and best “holy grail”.

There is a reason why the root word in “Workers’ Compensation” is “Work”; preventing injury, managing disability and disability forensics all take work. There is no magic bullet or formula.

Today’s health care cost containment providers, suppliers and vendors present new technologies to current or potential clients that often reflect an overly simplistic solution. The term “technology” for the purpose of this discourse is not restricted to equipment per se’, I.T., computer, Internet or cloud applications of software, digitization, “big data” etc. Technology in this context refers to the knowhow of developing innovative solutions through the application of knowledge.

I speak specifically, to the latest fad of viewing psychosocial issues as the next panacea for the management of medical costs especially in workers’ compensation. There is no question concerning the importance and prognostic value of analyzing and addressing psychosocial issues. I dedicated an entire chapter to this subject in a book and for thirty-six years have considered psychosocial and economic factors when treating a patient, performing a peer review or consulting directly with employers.

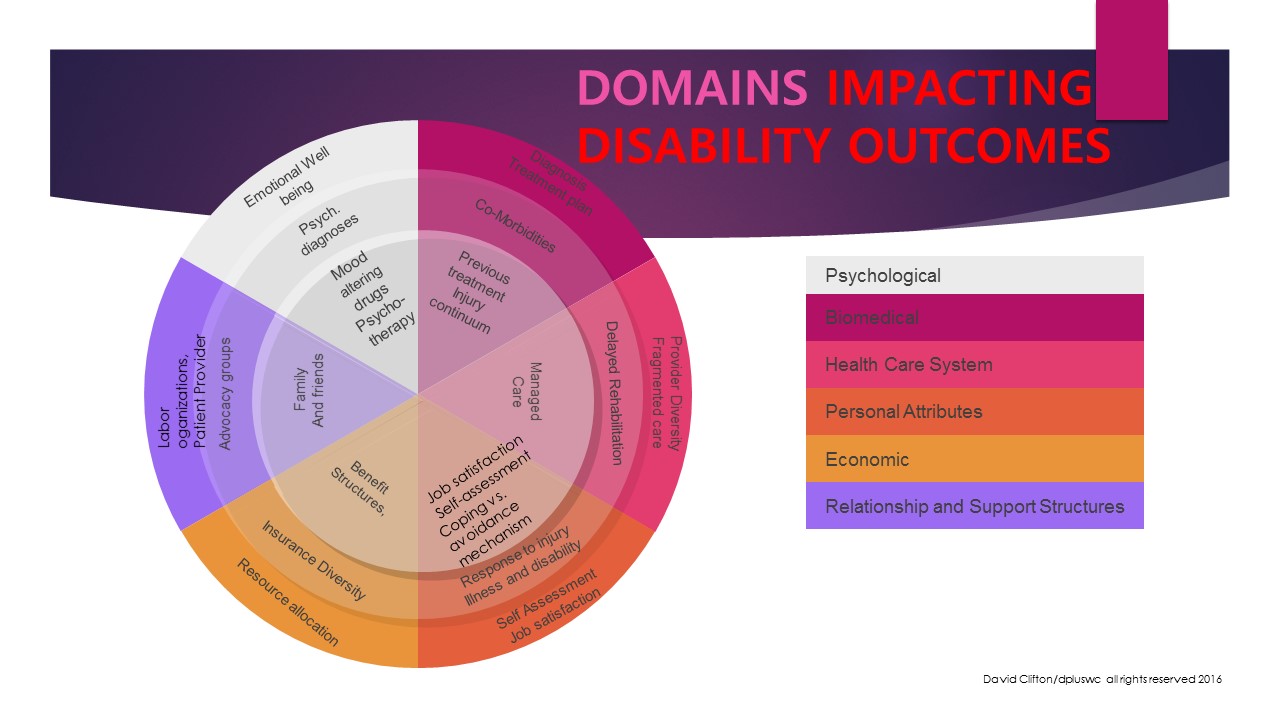

The criticality of psychosocial variables has been known for decades. Winston Churchill’s often recited quotation [but yet, to be documented in terms of attribution] frame the issue well; “You can always count on Americans to do the right thing, after they’ve done all of the wrong ones”. Despite overwhelming evidence in the clinical literature that the biomedical or pathophysiological approach to chronic musculoskeletal injuries has done little to alter the medical and indemnity costs we continue to direct our attention on the injury or pathology itself and not, the more prognostic manifestations or psychosocial consequences. My thirty-six years of clinical and peer review experience combined with a stint as a workers’ compensation casualty myself has taught me that the “regionalization” focus (e.g. low back patient, carpal tunnel case) is an abject failure because it does not incorporate a holistic view of a patient/client as a human being with multiple variables impacting who becomes disabled and who does not. We can continue to hurl the paint against the canvas like a loft studio artist hoping something will stick and that it will look great! Or, we can engage in a paradigm shift away from seeing our patients as body parts and shift to the real prognostic indicators. Workers compensation systems must wake up to the reality that psychosocial responses to injury/illness like post-traumatic stress disorder/PTSD in warriors takes its toll and we all will pay in one form or another.

Provider networks that squeeze cost savings from loosely aggregated providers [often pocketing most of the savings and not passing them along to employers and/or insurers] have run out of juice to squeeze. The reality is that many providers have adjusted their practice patterns, participate in voluntarily/involuntary pre-authorization of services, engage in evidenced-based medicine, align with capitation models of reimbursement and continuously strive to reduce their operational costs, e.g. use of extenders of care. The medical marketplace has been overpopulated with “middle men” organizations that drive very little real value and are more similar to the boardwalk shell game associated with trickster of years past.

As we continue to migrate away from the biomedical model of health care with its emphasis on pain and illness, the focus shifts more attention to what Fordyce called “extra dermal” influences. (Fordyce, 1997)

For those of us who practiced physical therapy in workers compensation systems (a legal system vs. medical system); it was considered absolute taboo to even mention that a patient/client may be experiencing a psychological or sociological barrier to recovery. To mention that a patient’s pain response might be in their head although, accurate (e.g. limbic system, thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex) would certainly result in fewer referrals to a therapist. Thank God there is more recognition and acceptance of the role played by non-medical variables in a successful return to work, optimization of physical functioning and quality of life. However, caution must be exercised when selecting assessment tools. A physical therapist would not select just one standing balance or gait assessment tool in order to determine a patient’s ability/disability status. Likewise, it may be risky to select one psychosocial measurement scale or questionnaire as a panacea to determine a patient’s return-to-work status. There is a reason why the clinical literature describes hundreds of assessment tools. Defensibility in the courtroom may ultimately determine the utility and true value of any assessment instrument or technology.

One notable inclusion on this list is the groundbreaking work performed at the Menninger Foundation by Hester and Decelles (1986). These researchers produced the “Menninger RTW Scale”, developed as a prognostic tool that assesses the impact of various non-medical issues on a patient’s recovery trajectory. Some of these issues include; age, gender, wage replacement, educational level, occupational category, disability severity, residence, marital status, employment status and support structures. Psychosocialconsiderations are additive not substitutions for conventional body system-based clinical measures: musculoskeletal, neurological, integumentary, cardiac and pulmonary. It is important to point out that conventional measures predict outcome disability scores in only 7% of all patients and in only 10% of patients with acute-stage back injury. (Burton et al, 1995). Whereas, psychosocial measures were significantly more predictive of who returned-to-work, at 32% across all patients and 59% in acute cases. These data suggest that persistence of symptoms in persons with low back conditions, especially in those with a previous history of back injury, may result more from psychosocial influences than from medical or biophysical issues.

“Early identification of psychosocial problems during the acute stage of irritability may potentially prevent some conditions from reaching the chronic stage”.

Exclusive use of any psychosocial predictive scales (low hanging fruit) without concurrent focus on medical or biophysical issues is destined to failure and relegation to the medical salvage heap if their use represents an oversimplification of an area that requires one thing more than any other….work!

References:

Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Main CJ et al: Psychosocial predictors of outcomes in acute and subacute low back trouble. Spine 20(2):722-728, 1995

Clifton DW, Physical Rehabilitation’s Role in Disability Management. St Louis: Elsevier/WB Saunders, 2005

Fordyce WE: Behavioral Methods for Chronic Pain and Illness. St Louis, Mosby, 1976

Hester EJ, Decelles P: Predicting Which Disabled Employees Will Return to Work: The Menninger RTW Scale. Topeka:KS, The Menninger Foundation Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Preventing Disability Dependence, 1986